I had the pleasure of going to New York to work on the pre-rendered game cinematics for the new Skylanders Giants for all console platforms including some unique stereoscopic sequences for the 3DS. The games are currently being splashed all over the Disney channels ready for the Christmas season.

I've written up a little about my experiences working on both sets of sequences here:

Skylanders Giants

Skylanders Giants 3DS

28 November 2012

27 November 2012

Cloud Catchers - Short Film

I've been working on Lucas Martell's "Cloud Catchers" short film. We've been good friends for a few years now but had yet to work together and I couldn't pass up this chance to blend our directing styles. I couldn't do it initially when he first asked me but as my schedule freed up I was able to slip in as the last recruited member of the team.

There will be more news on this project later on as it approaches completion over the coming months. In the mean time you might want to subscribe to the blog which will be updated in due time.

http://www.CloudCatchersFilm.com

Labels:

Cloud Catchers,

Lucas Martell,

Pigeon Impossible,

short film

26 November 2012

Production Tips - Recruiting Database

Continuing on from the last Production Tip blog about Tracking Production...

The Recruiting Database

This might seem creepy but I kept a spreadsheet with some basic information on everyone on the team... or anyone interested in joining the team. The key thing I used this for was to remember their strengths, up to years after I last had any contact with them. We had over 400 volunteers sign up and many more that I spoke to outside of our development site. It could get very difficult for me to remember every encounter, especially since most were only over email. I tended to remember shots in reels better than the specifics about my conversations with each artist. Some would be people that left the project and rejoined a year later, and it was key to remember their strengths and weaknesses.

I would score them in a few very important areas:

Talent (0 to 4) - The quality of their reel, this would be updated with each encounter and if their work on the film differed from the work in their reel.

Communication (0 to 3) - Their communication skills including written English and responsiveness. A world wide project can have some severe problems with basic languages. I don't speak anything other than English, so it was key that everyone on the team could both read and write really clearly in English in order to avoid hitting any brick walls. Equally the best written English in the world does no-one any favors if they don't answer their messages. Not replying is the same as not turning up to work in the virtual studio model!

Signed Up? (0 to 1) - Were they signed up on the development site? It was a sign of commitment and an openness to working in the pipeline we'd built. If they weren't willing to sign up then it was always a good sign that they were going to require extra effort on the part of the team to integrate them, and it usually wasn't worth it.

Score - This was a simple formula that multiplied up the scores above to give an overall rating. Then by ordering the spreadsheet by this number you could quickly see the best team members and candidates rising to the top.

Assigned - This simply kept tabs on whether they were currently assigned to something. It could take some people quite a while to complete a task and it was useful to have a quick look-up in the spreadsheet to see where things were getting stuck, or people were being left waiting for assignments.

The recruiting database is one of the few documents I didn't share with anyone. It's a very personal interpretation and could easily offend. But it was incredibly useful for me to head off any poor assignment choices, since I didn't really know most of the people working on the film (as I'd never met them in person). It was mostly animators as that was by far the largest area we got volunteers and required the most filtering (over 340 candidates). I imagine that similar databases exist in all the major studios, and the recruiters no doubt rely on them for every interaction. With any luck they're more sophisticated than my spreadsheet. The scary part is that recruiters move around between studios all the time so the data going into such a database isn't going to be consistent... food for though!

Other related blog entries of interest - Workload Distribution

Labels:

animation,

database,

excel,

producer,

recruiter,

recruiting,

spreadsheet

23 November 2012

Production Tips - Tracking Production

Kenny Roy asked me to contribute some anecdotes for a presentation he's putting on, and I thought it would be a good idea to share them here.

Tracking Production

I'm a keen addict of a good Excel spreadsheet that tracks the progress of each project. My short film was no different and over time I was able to show the progress of each department across the duration of the film.

I let Excel save out an image of two charts that were then synced to a public folder on Dropbox. The first just showed the progress level in the main categories It was published to our development website and quickly allowed anyone to see how far we were. It was also embedded into the beginning of the animatic edit. The image simply overwrote each time I saved so it was always up to date and showed up in each export of the animatic that I published about once every two weeks.

The second graph showed the progress over time. This was very useful as we could aim for a date and see roughly when departments were getting behind. It allowed me to respond by changing assignments, recruiting more or less in each skill set or simply redirect my own time to compensate.

Both charts helped to show a steady active progress so that the team never felt like they were alone, and that no-one else was pulling their weight. Including the publishing date in the images also showed they were up to date, and fortunately I was always very good about updating the spreadsheet. It becomes a bit of an addition watching those bars move closer to 100%. Since these films can take years they also tend to become a common conversation ice breaker between friends and it was handy to have a solid "42% Animated" or "67% Complete!" to show confidence in our progress. Constantly saying "nearly there" or "we're still animating" tends to feel like a downer and even though it's the same thing it casts doubts the more you repeat yourself without change. So take joy in the micro progress, and the sub-tasks you complete!

In the next production tip blog.... the Recruiting Database.

Other related blog entries of interest - At what point is the film most at risk?

Tracking Production

I'm a keen addict of a good Excel spreadsheet that tracks the progress of each project. My short film was no different and over time I was able to show the progress of each department across the duration of the film.

I let Excel save out an image of two charts that were then synced to a public folder on Dropbox. The first just showed the progress level in the main categories It was published to our development website and quickly allowed anyone to see how far we were. It was also embedded into the beginning of the animatic edit. The image simply overwrote each time I saved so it was always up to date and showed up in each export of the animatic that I published about once every two weeks.

The second graph showed the progress over time. This was very useful as we could aim for a date and see roughly when departments were getting behind. It allowed me to respond by changing assignments, recruiting more or less in each skill set or simply redirect my own time to compensate.

Both charts helped to show a steady active progress so that the team never felt like they were alone, and that no-one else was pulling their weight. Including the publishing date in the images also showed they were up to date, and fortunately I was always very good about updating the spreadsheet. It becomes a bit of an addition watching those bars move closer to 100%. Since these films can take years they also tend to become a common conversation ice breaker between friends and it was handy to have a solid "42% Animated" or "67% Complete!" to show confidence in our progress. Constantly saying "nearly there" or "we're still animating" tends to feel like a downer and even though it's the same thing it casts doubts the more you repeat yourself without change. So take joy in the micro progress, and the sub-tasks you complete!

In the next production tip blog.... the Recruiting Database.

Other related blog entries of interest - At what point is the film most at risk?

Labels:

animation,

excel,

producer,

production,

spreadsheet,

tracking

22 November 2012

21 November 2012

Updated Layout / Previs Demoreel

I've been doing a lot of spit and polish on my portfolio recently while hunting for work. Half of the shots in my Layout / Previs reel are new thanks to the release of Skylanders Giants.

Portfolio Website

Portfolio Website

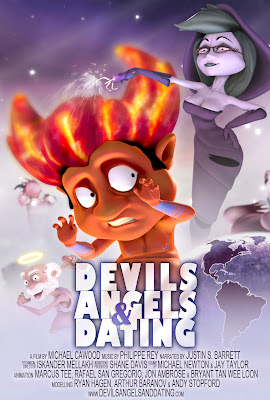

Devils Angels and Dating - Directors Cut

I had some niggling doubts about the pacing of the first half of the film and I decided it was worth the time to make a few easy fixes for this Directors Cut exclusively for Vimeo. It adds 30 seconds to the overall length and it's designed to clarify a few things.

Labels:

directors cut,

short film,

vimeo

Location:

Brooklyn, NY 11215, USA

11 September 2012

Guiding vs Micromanaging

This is a tough balance for any Director. You want to communicate your vision and give your team firm direction as they go along, but if you tell them how to do their job down to the finest detail there’s nothing for them to get any satisfaction from. They’ll quickly realize there’s no point in using their creativity, and problem solving skills, and they’ll lose their personal investment in the task. Then all you have is a clock punching drone, waiting to go home. But that’s in the work place. On a volunteer based film production it can mean you lose their interest entirely, and you lose a team member.

Since ‘Devils, Angels and Dating’ was produced entirely online I can’t even be sure when that happened to my team mates. I’m positive it must have occurred on some level for some people, as we had plenty of turnover with team members, like any volunteer based project. But without dealing with them in person it’s hard to figure out where that line is with each team member. Usually in person you can tell. Body language, mood and tone of voice are going to tell you a lot about how someone is taking your notes, but online it can often be too late before you realise its happening. That’s one major flaw with a virtual studio. It can be reduced by doing two things: 1) use people you know, as you’re much more likely to know their limits; 2) shoot video critiques occasionally so that they can tell which notes are important based on your body language; and 3) be very, very, cautious. Since the vast majority of people that volunteered on Devil’s weren’t people I knew, I was as cautious as I could be most of the time. The down side to this is that you constantly set a tone where you’re perhaps not the authority figure you should be to really follow through with a strong vision. Then things can get watered down and that definitely happened with Devils.

A great example of a shot injected with the animators own unique ideas, from Ryan Hagen.

I made up for it to some degree by plugging the gaps myself when things fell short; polishing shots, adjusting lighting, comps, rigging, effects, etc... But that brings us back to my earlier point; you’re taking ownership of the final product away from the artist, which in the long term means they don’t feel they can trust me (the Director) to deliver their small piece of the creative pie to the screen. Since that’s the primary reason most artists join a volunteer project that’s a problem.

I can comment on how these issues played out on a zero budget short film because there is no client, or studio to offend... essentially I was the client and the team was the studio. But this stuff is universal and applies to the everyday working world in almost every industry. A programmer is creatively solving problems all day, so they don’t want to lose much of their creative slice of the pie. A teacher may have problems with a student but it’s up to them to figure out how to best help the student... take that away and you’re taking their job satisfaction away. Some professions are more tolerant of this and it comes with the industry culture, but animation is inherently creative and a huge percentage of positions in the industry are expected to require some level of creativity. So Directors, Supervisors, Producers, etc... all have to be very careful to keep an eye on how they walk the line between guiding and micromanaging. The ones that succeed give just enough encouragement and direction to allow their team members to shine, which leads to personal investment in the product, enthusiasm and... yes... (the golden goose to employers) faster work and potentially longer hours put in to get it done!

I have also faced a different spin on this issue on several occasions. I’ll use my experiences on Devils as an example. As we had so many less experienced artists and animators working with us, I found that many of them hadn’t really worked in such isolation without a supervisor or teacher telling them every single step they needed to make. They could have amazing reels, but you realise that they did it with a lot of guidance (or effectively micromanaging). In this case it’s a heavy hand they actually wanted, perhaps it was school where every creative choice they made was monitored very closely and guided to the final product. At this point they’re not necessarily ready to do it alone yet, but that’s when I’ve found them volunteering on Devils for the experience (and the shots). It’s not new to me, mentoring lesser experienced animators, but it is considerably more time consuming and when you’re typing most of the feedback it can be very slow. We had up to 30 or 40 people coming to me for feedback at the project’s peek. Mix in too many people that need that level of feedback and suddenly I don’t have enough time to get to other tasks, and I might as well be doing it myself. So I’d often find myself in a position where I was recognising that I was micromanaging them too much to be efficient. At this point I occasionally experimented with holding back my notes enough to let them either succeed or fail on their own terms. Better, from my perspective, to let them fail and start the shot again with someone else, than to spend too much time on the first animator letting the rest of the film suffer (then the results still aren’t as strong as they could be). It’s a tough decision but as the Director, sometimes you have to make it. Sometimes you’ll get lucky and they’ll realise they have more scope to inject their own ideas and it’ll come out great, but usually if I’ve gotten to this point with someone, it would just become a waiting game until it was clear the shot needed to be approached again by someone else. This is one of the darkest moments you’ll have directing a team of volunteers. You don’t like to waste their time or yours, considering no-one is getting paid for it. Of course in a normal day job, when money is being spent, you don’t often have the luxury of letting someone fail, so it can be that much harder on the decision makers to decide when to cut your loses.

The other problem is that if you’re micromanaging they aren’t putting something of their own ideas and creativity into it, again watering down the potential strength of the film. I’m going to admit it... some of the very best animated shots in Devils were done by really good animators I could leave largely to their own devices and they would do things that I would never have considered. That’s exactly what you want. As long as they have a very clear idea what’s needed for the overall story, and that’s all a Director should need to convey (that includes style, character, continuity, pacing, etc...).

A great shot created with minimal supervision by talented animator, Marcus Tee Jin Liang

The best Directors surround themselves with talent that can bring something creative to the table, often even better than the Director’s own ideas. They give them everything they need to know and a touch of encouragement and guidance, but not so much as to take away from the talent’s own piece of the creative pie.

This is an important lesson I’ve been learning throughout my career, particularly as I found myself in a lead role so early on. I’d love to hear anyone else’s experiences on walking the line between guiding and micromanaging (if you’re able to talk about it without offending anyone).

Labels:

animated,

animation,

animator,

Director,

feedback,

filmmaking,

guiding,

lead,

management,

micromanaging,

producer,

short film,

supervisor,

volunteer

Location:

477-545 7th St, Brooklyn, NY 11215, USA

06 August 2012

The Layout Sandwich

I started my first full time job in animation and, along with another person starting the same day (later to become a close friend of mine), we found ourselves being taken into a large room with a cinema screen high up on one wall. We were sat down and told we’re about to see what we’re going to be making for the next six months. What we saw was (for its time) a very impressive action adventure role playing game filled with characters and cut-scenes (FMVs or cinematics as many prefer to refer to them).

It was my first day at Rare, a 200 strong, growing company with a very strong pedigree working under Nintendo’s wing. My friend and I were given an outline of what we’d be expected to start working on. He was a software engineer so we weren’t going to be doing the same things but we were going to be working together a lot. I was fully prepared to be doing in-game cycles, when the Director turned to me and casually told me I’d be making the cutscenes. I forget now if it was verbal, but I know that in my mind I went “Wahoooooo!”. It was more than most people could expect for their first job. I felt then, and now, that it was an incredible opportunity and I was very lucky. I guess all that hard work on my student short film must have paid off!

The game was about as story and character heavy as you could get at the time for the games industry, so I off to a great start. What’s more this wasn’t a company filled with story writers or filmmakers, even character development was in it’s infancy. We were aiming to make this game for the Nintendo 64 at the time so expectations weren’t high in those areas. So I found myself becoming incredibly valuable to the team, almost instantly taking over all the cinematics for the game. I wasn’t writing the scripts but I was creating sequences from script (and dialog performance) to screen, which gave me a lot of scope with which to play filmmaker.

That six month project grew and grew until it consumed three and a half years of my life! It turned out there were problems with this dream job, but that’s another story. What came out of it was an opportunity for me to create hours and hours worth of sequences with a wide variety of subject matter, characters and moods. I was working with dinosaurs, creatures, bipeds, quadrupeds, huge vista’s, tight caves, flight, stampedes, battles, puzzles, life, death, loss, jubilation, conflict and family. It was an epic start for a young animated filmmaker and presented me with so many opportunities to try things out.

That game completed with over two hours of cutscenes, all of which I’d been involved with (although a significant number where largely made by a friend of mine that joined the team for a couple of years). But I knew that there was more to it than that. Because of the troubles we faced over the years developing the game, I’d actually created in excess of, what I’m estimating, over ten hours of sequences! These were scenes that only my co-workers will ever have seen, and there are some firm favourites in there that I can still remember that will probably never be seen. I learned then just how much you have to iterate to get things to the screen. I learned to become less precious about the early stages of creating a sequence of shots and more open to change.

One thing I will say is that I wasn’t directed heavily at all during those years. Never since then have I had that much freedom, and you generally shouldn’t expect it... actually you don’t want it, as what you really want is a Director that knows what they want and teaches you as you go. In hindsight it was a valuable period of exploration, but I was self teaching which takes longer than being taught by a mentor. I didn’t have access to a library of films or books to look learn from, there was no internet or email to pass teaching around. It was all about trying things. I developed my own unique bag of filmmaking tricks to deal with things as I went along learning the slow way. I’d later find out these where known filmmaking rules. Of course I’d already read a good number of film making and cinematography books during my studies before i got the job, but there’s no substitute for practicing it yourself, and there’s no faster, cheaper and more immediate way to experiment than real-time game cinematics. What I was doing was effectively the precursor to today’s Machinema, and to top it off I had programmers bent on developing the tools for me to do an even better job and they were taking requests almost exclusively from me!

So what? I got off to a good start? Well yes but it was a small bubble too, and there was a lot I wasn’t learning about.

I moved onto another game and this time focused most of my time on 25 minutes of pre-rendered cinematics, while supervising other animators to make the in-game animation and other real-time cutscenes. That was to be the next three years. Those 25 minutes were filled with a similar range of opportunities, but his time I had the luxury of using ‘off the shelf’ tools, and working outside of the code base, which was even more freeing as I wasn’t dependant on programmers to get my work to the screen.

It gave me some the portfolio pieces to move onto other places, and so began the rest of my career in animation. But no matter how much I tried one thing stayed consistent. Although I may have been officially hired as an animator, I would almost never spend most of my time animating. So I was forced to learn other areas around animation. Over time I figured out that although I could be good at a lot of things it was the creation of story, a sequence of shots, the cinematography, layout, staging, timing and editing that really made me stand out. I was an animated filmmaker.

It was then that I started to make my short film, ‘Devils, Angels and Dating’, largely as a way to showcase all of my new skills into something I could call my own. I already had dozens of student films from before my days as a professional animator but they were very dated, created with very old software and styles (I was originally trained as a 2D animator). So with hours and hours of screen time under my belt I set about creating my own all new film, ideally a one minute master piece.... Ha! Yeah right! I could never do just a minute, I’m way to ambitious for that and at the time I just had too much pent up creative energy. I knew then and now that a minute was enough and would have been a smarter choice but it was like trying to contain a raging bull. I had a lot to say and too many skills to show off.

So after a couple of years of story and character design development, I had to get started. I started with thumbnail storyboards. I scanned them in and edited them together. This went back and forth for a while as the rest of the production took shape over at the development website with our growing team of volunteers. I actually published most of these edits to the web so that; 1) the team could see how it was shaping up, 2) I could get feedback, 3) attract talent and, 4) an audience. In all there were around a hundred or so versions of the animatic on YouTube that you can still to this day review to see how the film developed. This is one of the earliest animatics.

I was given filmmaking notes as I went along, but for the most part I was leaning on my own layout and staging experience leading up to this point. Acting as the principle artist, generalist and director of a film while also having a day job and having a life is an enormous strain. So I tried to find other people to help with Layout to get things into going faster (I had more animation volunteers than I could keep fed with shots). It was clear that I couldn’t get the animators to just create shots from storyboards, the results would have been extremely varied and the project would have been a nightmare. I did get some help from my good friend Kurt Lawson, with whom I spent some long work sessions side by side churning out shots in 3D. But in the end I had to do most of it, as for most people in this industry it’s not a task many people want spend their free time doing. So it became an ongoing task to keep a good number of shots prepared ahead of the wave of animators wanting to work on the film. It was also beneficial for me to handle most of the shots because I could keep a tight handle on the way the shots cut together and the way the camera movement flowed across the cut. Taking this task back myself had another unanticipated but very important benefit.

Any production is filled with people from different backgrounds, and wildly different levels of quality. Wrangling all those differences is challenging enough, but when you’re making something with nothing but volunteers (from all over the world) with no budget the variation goes off the chart. This is where most volunteer animated short film productions crumble and disappear.

So Layout and Final Layout came to the rescue and formed what I like to call the ‘sandwich of the production’. If animation is the content of the sandwich, the part you came for, then Layout and Final Layout are the slices of bread either side of it that holds it all together and makes it solid consumable product.

Layout is often referred to as a number of other names like Camera Staging, Previs, Setup and Workbook Layout. They are all variations around the same central 3D filmmaking problems to be solved. But in my case it essentially involved referencing in all the assets needed for a shot, staging their positions and broad movements through the scene while figuring out how the camera will frame them. The whole thing is playblasted out (animator talk for making a video) and saved as version one of the shot. The playblasts are put into the animatic replacing the storyboard panels. There will usually be a lot of back and forth re-iterations of each shot as the edit takes shape.

A long time ago I started keeping the edit open in the background as I work out the shots in 3D, and I’d just keep replacing the playblast videos and updating the timeline to get a fast turnaround. I still, to this day, don’t see enough of that being done on most productions and the lag between seeing a shot in 3D and seeing it in the edit can be excruciating to me. Anyway, for me it was a very efficient workflow and in time I filled up folders with scene files ready for animators to take over. This left little to chance, they couldn’t use the wrong assets, import it instead of referencing it or use the wrong part of the set, etc... Ultimately, along with the shot briefing and the animatic the animators had the vast majority of their questions answered for them and they could focus on the performances.

When the animators were done with the scene and it came back it was almost never ready to light and render. Each animator had a different level and style of polish, so animation did need some tweaks to keep it consistent and up to the same standards. But a 3D scene is so complex there’s also a huge number of things an animator can do that’s different from the next guy and it was necessary to check each scene over and make sure they all worked in the same way for the lighting and rendering pipeline.

The best perk of taking the shots back in for a final check-up was the ability to refine the camera based on the performance and any new shots that were completing either side of it. I could take a higher level look at each shot in the context of the edit and paint in broad strokes the style of the camera. I almost never changed the point of view of the camera, since that affects the performance too much and that was always locked down before the animator started. But I could push in a little, pull back a little, reframe the composition a bit or add camera shake and wobble. I actually designed a gradual flowing change of style of the camera work throughout the film to match the mood of the film. This is something that dozens of individuals focused exclusively on one shot each just can’t really co-ordinate. So it acted as a unifying process both artistically and technically. If anything I wish I could have been more ambitious with the camera work but at the time I was fighting a balancing act of making sure everyone could understand the production so that I could attract good talent, so I kept things simple.

I’d recommend the ‘Layout Sandwich’ practice to any animated film production, but I’ve seen firsthand how often it doesn’t work like this. Storyboards are rushed or skipped entirely. Projects are under too much pressure to finish yesterday, with too few people putting enough time into each step, or simply a lack of people with the Layout skillset being stretched too far. Work gets done, and then sent back to be re-done when it doesn’t work... but that’s another story.

So what’s the take away from all this? Layout is so much more than the poor animator’s fall back job. It’s pivotal to a production. I find myself more often than animating, creating and re-working sequences of shots because that’s where I’m needed the most. I tip my hats to the unsung heroes toiling away in studios around the world generating many iterations of shots most people will never see, so that both the audiences, and the animators, can understand a sequence. It’s a high art into itself, and solves so many problems. It takes a really specific skillset, while still understanding a broad number of factors to get it right. It’s one of the main balancing acts that holds animated productions together.

What are your Layout/Camera/Staging/Previs stories? I’m curious to learn more from the unsung heroes of the animated filmmaking world.

Labels:

animation,

animator,

Camera,

Director,

filmmaking,

Layout,

Layout Artist,

Previs,

Previsualisation,

short film,

Staging,

VFX,

Workbook Layout

Location:

Brooklyn, NY 11215, USA

29 July 2012

The right time to get story feedback

There’s

mixed stories about when you should get feedback on your ideas. In animation

it’s common for people to say that you should get feedback early and often but

I’d argue that’s not always true. If you do that you risk ‘too many cooks’ and

you can water down the elements that would make the film what it needs to be to

make it resonate with a targeted audience. Better instead to protect the idea,

and explore it fully for as long as you can, taking breaks so that you come

back to it fresh and with other perspectives filtered through you. Only when

you’re returning to it repeatedly from a fresh perspective and you feel it’s

gone as far as it can, is it time to get feedback.

At this

point it’s time to ask yourself if you have surrounded yourself with the kind

of people that can give you valuable, constructive feedback. Whether you

recognise it or not, your idea is still fragile and undeveloped and other

people will see it. You need to be sure that the next person that sees it

understands the fragile nature of an early idea and that they can both approach

your request for feedback with the appropriate level of care, while still

seeing the big picture and guiding you to a better place.

When I started

making Devil’s Angels & Dating I wanted nothing more than to share my idea

with other creative’s around me to get notes. But looking back now I realise I

was seeking a partner that could fill the gaps in my knowledge, bringing the

project up to a higher level without necessarily putting in the work myself. It

wasn’t that I was lazy. I was trying to do so many different things to get the

film made on top of having a life and a full time job. I accepted that I didn’t

know everything and I wanted to find a partner that would compliment my skills

and bring the project up to the standards I held myself to in all other areas

of the project. That sort of person is very hard to come by, and even when I

recognised the same spirit in other filmmakers, writers and artists there was

frequently a friction of egos. Anyone that

talented doesn’t easily commit themselves to an idea that’s not their own. So

my pursuit of a partner turned more into an opportunity to share filmmaking

lessons that informed the way I handled the making of my own film.

But still I

didn’t have the fresh eyes that were going to help me refine a masterful

script. From an early stage I gave it to other writers, writer’s muses,

artists, family members, friends, etc... and in the process of putting the

making of the film online even opened it up to strangers to comment on my

story. Some of the people I would have expected the best notes from gave me off

target notes like screenwriting formatting tips which was a bit disappointing.

Some of the best notes came from non writers, some notes came not from what

they said but by identifying what it was they saw in it that I couldn’t have

expected. Usually the best notes are what you interpret from their reaction,

not the specifics of what they think the solutions should be.

I did

manage to use some of the notes I got to steer the film towards a better

version but I also had too many notes from the wrong people too early and (combined

with my own insecurities at the time) it watered down the story and the themes

I was passionate about. This is a question of being strong as a creator, making

good choices and hand picking that best notes without losing sight of what’s

important to the project for you. Isolated from much of a support system it was

easy for me to find myself catering to peer pressure from strangers who’s

opinions I shouldn’t perhaps have put so much stock in. After all they didn’t

really see, understand or have faith in what I was really trying to do. So I

look back now and I know it’s not a pure as I wanted it to be. An easy indictor

of this is that the film is laden with props designed to serve one purpose or

another and I’ve always hated films that put so much emphasis on the importance

of magic borbals! The Indiana Jones films are the only ones I let get away with

it, primarily because those items tie directly into stories I grew up with...

but generally I prefer characters and situations to drive the narrative over

props.

Over time I

did find some good people to give me notes, and they gave great stuff. Usually

not at length, but just enough to steer me in a new direction that would

enhance the film, and usually that’s all you really want. A total re-write or

re-conceiving the idea can be completely destructive to the creative flow of a

project, but a firm guidance in a positive new directions can be very helpful.

The irony

is that most of the best notes came well after I’d already gone too far to turn

things around. Mostly after assets were made, animation had started, and the

team was well under way. Since this was a project with no budget and only the

services of volunteers bringing it to life, I had to be respectful about just

how much I changed. It was only when the project had a following, some

recognition and more than enough material to show that the people with the

notes that could have made a difference took the time to make themselves heard.

I knew that would happen to some degree and that’s why I persevered towards

getting it made even without strong feedback, as you can’t attract talent until

you’ve proved you’re not wasting their time. Now I would argue that I’ve made

my mark as a filmmaker to some degree and I do know people that would give me

gold if I needed feedback. But it’s taken a herculean effort to get here

including moving and changing jobs numerous times, being open to new

experiences and points of view.

So what

tips can I share with you?

1) Surround

yourself with good people... and if you can’t find them, seek them out. It may

require picking up your life and going elsewhere, certainly in the early

stages. You’re going to have to earn the respect of those people too.

2) Choose

the right time to get feedback... too early and you water down the story’s

voice, too late and it’s damaging to your creative flow to change it.

3) One last

tip; recognise what you want to get out of the feedback. Ask specific questions

to guide them to give you the level of feedback you’re looking for and get them

started. Don’t present them with a blank page and a “What do you think?” That’s

the same as asking someone for hours of their time and they have to believe

that they can help you in a meaningful way in a matter of minutes (unless they

are a really good friend).

Labels:

animation,

feedback,

filmmaking,

friends,

notes,

screenwriting,

short film,

story

Location:

Brooklyn, NY 11215, USA

05 July 2012

The Origins of a Man on a Mission

Devils

started out in the skies between Sydney and London. I’d spent years trying to

get into film after five years studying animation, followed by seven years

working in games. Finally I got an opportunity to work on my first film for a meager four months or so in Australia. The risk I’d taken to walk away from my

games job to do this seemed immense at the time, and it was meant to be the

beginning of something big. But what I came back with wasn't an incredible new reel

or a foot in the door at a film studio, I wasn't rich, and I hadn't learned

much more to further my animation skills. Instead I came back with an insight into

how much further I had to go, how much harder I had to work, how much more I

had to climb to get to where I wanted to be. But I also got a glimpse into how

much competition there was and how far I’d fallen behind the curve. I’d left

University at a level I felt was well above the norm... later in life you realize that’s how a lot of bright graduates feel only to be crushed by the real

world. In my case, I’d walked into a big company in the countryside that acted

like a protected bubble and I had no idea just what I was missing elsewhere in

the world. I worked for seven years away from good internet access, before

broadband was really taking off. I had an email address, but I was lucky if I

checked it once a week! Those few months working amongst so many animators

inspired me to take an even bigger series of risks. On the plane coming back

from Sydney, I put aside the feature length story I’d been toying with over the

years, and started dreaming up ideas for something I was actually going to be

able to make, and the inspiration for ‘Devils, Angels & Dating’ was born.

04 July 2012

Devils Angels & Dating at Grauman's Chinese Theatre

I thought I'd kick off my official blog posts here on blogger by showcasing our short film, 'Devils Angels and Dating'. It'll be screening at Grauman's Chinese Theatre in Hollywood on the 16th of August at the HollyShorts festival.

It's been amazing to have two articles in 3D World, and two in 3D Artist.

http://devilsangelsanddating.ning.com/photo/albums/press

Here's our official website where you can see lots of behind the scenes content.

http://www.DevilsAngelsAndDating.com/

It's been amazing to have two articles in 3D World, and two in 3D Artist.

http://devilsangelsanddating.ning.com/photo/albums/press

Here's our official website where you can see lots of behind the scenes content.

http://www.DevilsAngelsAndDating.com/

Labels:

animated,

animation,

animator,

cupid,

dating,

devils,

devils angels and dating,

short film

Location:

New York, NY, USA

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)